Nuremberg Trials

| The Holocaust |

|---|

Part of: Jewish history

|

|

Responsibility

Nazi Germany

People

OrganizationsAdolf Hitler Heinrich Himmler Ernst Kaltenbrunner Theodor Eicke Reinhard Heydrich Adolf Eichmann Odilo Globocnik Rudolf Höss Christian Wirth Nazi Party Schutzstaffel (SS) Gestapo Sturmabteilung (SA) Collaborators during

World War II Nazi ideologues

|

|

Early policies

Racial policy of Nazi Germany

Haavara Agreement Nuremberg Laws Nazi eugenics Action T4 Madagascar Plan Wannsee Conference |

|

The victims

Jews in Europe

Jews in Germany Romani people (Gypsies) Homosexuals People with disabilities Slavs in Eastern Europe Poles · Serbs Soviet POWs Jehovah's Witnesses |

|

The ghettos

List of ghettos

|

|

Atrocities

Pogroms

Kristallnacht · Bucharest Dorohoi · Iaşi · Jedwabne Kaunas · Lviv (Lvov) Vel' d'Hiv · Wąsosz End of World War II

Death marches · Berihah |

|

The camps

Nazi concentration camps

Bergen-Belsen · Bogdanovka Buchenwald Dachau · Gross-Rosen Herzogenbusch Janowska · Jasenovac Kaiserwald Maly Trostenets Mauthausen-Gusen Neuengamme · Ravensbrück Sachsenhausen · Sajmište Salaspils · Stutthof Theresienstadt Uckermark · Warsaw List of Nazi concentration

camps |

|

Resistance

Jewish partisans

|

|

Aftermath

Nuremberg Trials

Denazification Surviving Remnant Reparations Agreement

between Israel and West Germany |

|

Lists

Holocaust survivors

Victims of Nazism Rescuers of Jews |

|

Resources

The Destruction of

the European Jews Functionalism versus

intentionalism |

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the main victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany. The trials were held in the city of Nuremberg, Bavaria, Germany, in 1945-46, at the Palace of Justice. The first and best known of these trials was the Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal (IMT), which tried 22 of the most important captured leaders of Nazi Germany. It was held from November 20, 1945 to October 1, 1946. The second set of trials of lesser war criminals was conducted under Control Council Law No. 10 at the US Nuremberg Military Tribunals (NMT); among them included the Doctors' Trial and the Judges' Trial. This article primarily deals with the IMT; see the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials for details on those trials.

Contents |

Origin

British War Cabinet documents, released on 2 January 2006, have shown that as early as December 1944, the Cabinet had discussed their policy for the punishment of the leading Nazis if captured. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had then advocated a policy of summary execution in some circumstances, with the use of an Act of Attainder to circumvent legal obstacles, being dissuaded from this only by talks with US leaders later in the war. In late 1943, during the Tripartite Dinner Meeting at the Tehran Conference, the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, proposed executing 50,000–100,000 German staff officers. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, joked that perhaps 49,000 would do. Churchill denounced the idea of "the cold blooded execution of soldiers who fought for their country." However, he also stated that war criminals must pay for their crimes and that in accordance with the Moscow Document which he himself had written, they should be tried at the places where the crimes were committed. Churchill was vigorously opposed to executions "for political purposes."[1][2] According to the minutes of a Roosevelt-Stalin meeting during the Yalta Conference, in February 4, 1945, at the Livadia Palace, President Roosevelt "said that he had been very much struck by the extent of German destruction in the Crimea and therefore he was more bloodthirsty in regard to the Germans than he had been a year ago, and he hoped that Marshal Stalin would again propose a toast to the execution of 50,000 officers of the German Army."[3]

US Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., suggested a plan for the total denazification of Germany; this was known as the Morgenthau Plan. The plan advocated the forced de-industrialisation of Germany. Roosevelt initially supported this plan, and managed to convince Churchill to support it in a less drastic form. Later, details were leaked to the public, generating widespread protest. Roosevelt, seeing strong public disapproval, abandoned the plan, but did not proceed to adopt support for another position on the matter. The demise of the Morgenthau Plan created the need for an alternative method of dealing with the Nazi leadership. The plan for the "Trial of European War Criminals" was drafted by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and the War Department. Following Roosevelt's death in April 1945, the new president, Harry S. Truman, gave strong approval for a judicial process. After a series of negotiations between the Britain, US, the Soviet Union and France, details of the trial were worked out. The trials were set to commence on 20 November 1945, in the Bavarian city of Nuremberg.

Creation of the courts

On January 14, 1942, representatives from the nine occupied countries met in London to draft the Inter-Allied Resolution on German War Crimes. At the meetings in Tehran (1943), Yalta (1945) and Potsdam (1945), the three major wartime powers, the United Kingdom, United States, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics agreed on the format of punishment for those responsible for war crimes during World War II. France was also awarded a place on the tribunal.

The legal basis for the trial was established by the London Charter, issued on August 8, 1945, which restricted the trial to "punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis countries." Some 200 German war crimes defendants were tried at Nuremberg, and 1,600 others were tried under the traditional channels of military justice. The legal basis for the jurisdiction of the court was that defined by the Instrument of Surrender of Germany. Political authority for Germany had been transferred to the Allied Control Council which, having sovereign power over Germany, could choose to punish violations of international law and the laws of war. Because the court was limited to violations of the laws of war, it did not have jurisdiction over crimes that took place before the outbreak of war on September 3, 1939.

Location

Leipzig, Munich and Luxembourg were briefly considered as the location for the trial.[4] The Soviet Union had wanted the trials to take place in Berlin, as the capital city of the 'fascist conspirators'[4], but Nuremberg was chosen as the site for the trials for specific reasons:

- The Palace of Justice was spacious and largely undamaged (one of the few buildings that had remained largely intact through extensive Allied bombing of Germany). A large prison was also part of the complex.

- Nuremberg was considered the ceremonial birthplace of the Nazi Party, and hosted annual propaganda rallies.[4] It was thus a fitting place to mark the party's symbolic demise.

As a compromise with the Soviet Union, it was agreed that while the location of the trial would be Nuremberg, Berlin would be the official home of the Tribunal authorities.[5][6][7]

It was also agreed that France would become the permanent seat of the IMT[8] and that the first trial (several were planned) would take place in Nuremberg.[5][7]

Participants

Each of the four countries provided one judge and an alternate, as well as the prosecutors.

Judges

Major General Iona Nikitchenko (Soviet main)

Major General Iona Nikitchenko (Soviet main) Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Volchkov (Soviet alternate)

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Volchkov (Soviet alternate) Colonel Sir Geoffrey Lawrence (British main and president)

Colonel Sir Geoffrey Lawrence (British main and president) Sir Norman Birkett (British alternate)

Sir Norman Birkett (British alternate) Francis Biddle (American main)

Francis Biddle (American main) John J. Parker (American alternate)

John J. Parker (American alternate) Professor Henri Donnedieu de Vabres (French main)

Professor Henri Donnedieu de Vabres (French main) Robert Falco (French alternate)

Robert Falco (French alternate)

The chief prosecutors

Sir Hartley Shawcross (United Kingdom)

Sir Hartley Shawcross (United Kingdom) Robert H. Jackson (United States)

Robert H. Jackson (United States) Lieutenant-General Roman Andreyevich Rudenko (Soviet Union)

Lieutenant-General Roman Andreyevich Rudenko (Soviet Union) François de Menthon (France)

François de Menthon (France)

Assisting Jackson was the lawyer Telford Taylor and a young US Army interpreter named Richard Sonnenfeldt. Assisting Shawcross were Major Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe and Sir John Wheeler-Bennett. Mervyn Griffith-Jones, later to become famous as the chief prosecutor in the Lady Chatterley's Lover obscenity trial, was also on Shawcross's team. Shawcross also recruited a young barrister, Anthony Marreco, who was the son of a friend of his, to help the British team with the heavy workload. Assisting de Menthon was Auguste Champetier de Ribes.

Defense Counsel

The majority of defense attorneys were German lawyers.

The main trial

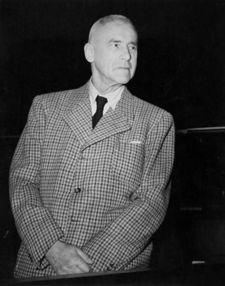

The International Military Tribunal was opened on October 18, 1945, in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg.[9] The first session was presided over by the Soviet judge, Nikitchenko. The prosecution entered indictments against 24 major war criminals and six criminal organizations – the leadership of the Nazi party, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the Gestapo, the Sturmabteilung (SA) and the "General Staff and High Command," comprising several categories of senior military officers.

The indictments were for:

- Participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of a crime against peace

- Planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression and other crimes against peace

- War crimes

- Crimes against humanity

The 24 accused were, with respect to each charge, either indicted but acquitted (I), indicted and found guilty (G), or not charged (O), as listed below by defendant, charge, and eventual outcome:

| Name |

|

Penalty | Notes | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

Martin Bormann |

I | O | G | G | Death | Successor to Hess as Nazi Party Secretary. Sentenced to death in absentia. Remains found in Berlin in 1972 and dated to 1945.[10] |

Karl Dönitz |

I | G | G | O | 10 years | Leader of the Kriegsmarine from 1943, succeeded Raeder. Initiator of the U-boat campaign. Became President of Germany following Hitler's death.[11] In evidence presented at the trial of Karl Dönitz on his orders to the U-boat fleet to breach the London Rules, Admiral Chester Nimitz stated that unrestricted submarine warfare was carried on in the Pacific Ocean by the United States from the first day that nation entered the war. Dönitz was found guilty of breaching the 1936 Second London Naval Treaty, but his sentence was not assessed on the ground of his breaches of the international law of submarine warfare.[12] Defense attorney: Otto Kranzbühler |

Hans Frank |

I | O | G | G | Death | Reich Law Leader 1933–1945 and Governor-General of the General Government in occupied Poland 1939–1945. Expressed repentance.[13] |

Wilhelm Frick |

I | G | G | G | Death | Hitler's Minister of the Interior 1933–1943 and Reich Protector of Bohemia-Moravia 1943–1945. Authored the Nuremberg Race Laws.[14] |

Hans Fritzsche |

I | I | I | O | Acquitted | Popular radio commentator; head of the news division of the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. Tried in place of Joseph Goebbels.[15] |

Walther Funk |

I | G | G | G | Life Imprisonment | Hitler's Minister of Economics; succeeded Schacht as head of the Reichsbank. Released because of ill health on 16 May 1957.[16] Died 31 May 1960. |

|

G | G | G | G | Death | Reichsmarschall, Commander of the Luftwaffe 1935–1945, Chief of the 4-Year Plan 1936–1945, and original head of the Gestapo before turning it over to the SS in April 1934. Originally Hitler's designated successor and the second highest ranking Nazi official.[17] By 1942, with his power waning, Göring fell out of favor and was replaced in the Nazi hierarchy by Himmler. Committed suicide the night before his execution.[18] |

|

G | G | I | I | Life Imprisonment | Hitler's Deputy Führer until he flew to Scotland in 1941 in attempt to broker peace with Great Britain. After trial, committed to Spandau Prison; died in 1987.[19] |

|

G | G | G | G | Death | Wehrmacht Generaloberst, Keitel's subordinate and Chief of the OKW's Operations Division 1938–1945. Subsequently exonerated by German court in 1953, though the exoneration was later overturned, largely as a result of pressure by American officials.[20] |

|

I | O | G | G | Death | Highest surviving SS-leader. Chief of RSHA 1943–45, the Nazi organ made up of the intelligence service, Secret State Police and Criminal Police. Also had overall command over the Einsatzgruppen and several concentration camps.[21] |

|

G | G | G | G | Death | Head of Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) 1938–1945.[22] |

|

I | I | I | ---- | Major Nazi industrialist. C.E.O of Krupp A.G 1912–45. Medically unfit for trial (died January 16, 1950). The prosecutors attempted to substitute his son Alfried (who ran Krupp for his father during most of the war) in the indictment, but the judges rejected this as being too close to trial. Alfried was tried in a separate Nuremberg trial for his use of slave labor, thus escaping the worst notoriety and possibly death. | |

|

I | I | I | I | ---- | Head of DAF, The German Labour Front. Suicide on 25 October 1945, before the trial began. |

Baron Konstantin von Neurath

|

G | G | G | G | 15 years | Minister of Foreign Affairs 1932–1938, succeeded by Ribbentrop. Later, Protector of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–43. Resigned in 1943 because of a dispute with Hitler. Released (ill health) 6 November 1954[23] after having a heart attack. Died 14 August 1956. |

|

I | I | O | O | Acquitted | Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and Vice-Chancellor under Hitler in 1933–1934. Ambassador to Austria 1934–38 and ambassador to Turkey 1939–1944. Although acquitted at Nuremberg, von Papen was reclassified as a war criminal in 1947 by a German de-Nazification court, and sentenced to eight years' hard labour. He was acquitted following appeal after serving two years.[24] |

|

G | G | G | O | Life Imprisonment | Commander In Chief of the Kriegsmarine from 1928 until his retirement in 1943, succeeded by Dönitz. Released (ill health) 26 September 1955.[25] Died 6 November 1960. |

|

G | G | G | G | Death | Ambassador-Plenipotentiary 1935–1936. Ambassador to the United Kingdom 1936–1938. Nazi Minister of Foreign Affairs 1938–1945,[26] |

|

G | G | G | G | Death | Racial theory ideologist. Later, Minister of the Eastern Occupied Territories 1941–1945.[27] |

Fritz Sauckel

|

I | I | G | G | Death | Gauleiter of Thuringia 1927–1945. Plenipotentiary of the Nazi slave labor program 1942–1945.[28] Defense attorney: Robert Servatius |

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht

|

I | I | O | O | Acquitted | Prominent banker and economist. Pre-war president of the Reichsbank 1923–1930 & 1933–1938 and Economics Minister 1934–1937. Admitted to violating the Treaty of Versailles.[29] |

Baldur von Schirach

|

I | O | O | G | 20 years | Head of the Hitlerjugend from 1933 to 1940, Gauleiter of Vienna 1940–1943. Expressed repentance.[30] |

|

I | G | G | G | Death | Instrumental in the Anschluss and briefly Austrian Chancellor 1938. Deputy to Frank in Poland 1939–1940. Later, Reich Commissioner of the occupied Netherlands 1940–1945. Expressed repentance.[31] |

|

I | I | G | G | 20 Years | Hitler's favorite architect and close friend, and Minister of Armaments from 1942 until the end of the war. In this capacity, he was ultimately responsible for the use of slave laborers from the occupied territories in armaments production. Expressed repentance.[32] |

|

I | O | O | G | Death | Gauleiter of Franconia 1922–1940. Publisher of the weekly newspaper, Der Stürmer.[33] |

Throughout the trials, specifically between January and July 1946, the defendants and a number of witnesses were interviewed by American psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn. His notes detailing the demeanor and comments of the defendants survive; they were edited into book form and published in 2004.[34]

The death sentences were carried out 16 October 1946 by hanging using the standard drop method instead of long drop.[35][36] The U.S. army denied claims that the drop length was too short which caused the condemned to die slowly from strangulation instead of quickly from a broken neck.[37]

The executioner was John C. Woods. Although the rumor has long persisted that the bodies were taken to Dachau and burned there, they were actually incinerated in a crematorium in Munich, and the ashes scattered over the river Isar.[38] The French judges suggested the use of a firing squad for the military condemned, as is standard for military courts-martial, but this was opposed by Biddle and the Soviet judges. These argued that the military officers had violated their military ethos and were not worthy of the firing squad, which was considered to be more dignified. The prisoners sentenced to incarceration were transferred to Spandau Prison in 1947.

Of the 12 defendants sentenced to death by hanging, two were not hanged: Hermann Göring committed suicide the night before the execution and Martin Bormann was not present when convicted (he had, unbeknownst to the Allies, committed suicide in Berlin in 1945). The remaining 10 defendants sentenced to death were hanged.

The definition of what constitutes a war crime is described by the Nuremberg Principles, a set of guidelines document which was created as a result of the trial. The medical experiments conducted by German doctors and prosecuted in the so-called Doctors' Trial led to the creation of the Nuremberg Code to control future trials involving human subjects, a set of research ethics principles for human experimentation.

Of the organizations the following were found not to be criminal:

- Reichsregierung

- "The General Staff and High Command" was found not to comprise a group or organization as defined by Article 9 of the London Charter

- Sturmabteilung

Legacy

The creation of the IMT was followed by trials of lesser Nazi officials, trials of Nazi doctors, who performed horrifying experiments on people in prison camps. It served as the model for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East which tried Japanese officials for crimes against peace and against humanity. It also served as the model for the Eichmann trial and for present-day courts at The Hague, for trying crimes committed during the Balkan wars of the early 1990s, and at Arusha, for trying the people responsible for the genocide in Rwanda.

The Nuremberg trials had a great influence on the development of international criminal law. The Conclusions of the Nuremberg trials served as models for:

- The Genocide Convention, 1948.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

- The Nuremberg Principles, 1950.

- The Convention on the Abolition of the Statute of Limitations on War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, 1968.

- The Geneva Convention on the Laws and Customs of War, 1949; its supplementary protocols, 1977.

The International Law Commission, acting on the request of the United Nations General Assembly, produced in 1950 the report Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal and in the Judgement of the Tribunal (Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1950, vol. II[39]). See Nuremberg Principles.

The influence of the tribunal can also be seen in the proposals for a permanent international criminal court, and the drafting of international criminal codes, later prepared by the International Law Commission.

Establishment of a permanent International Criminal Court

The Nuremberg trials initiated a movement for the prompt establishment of a permanent international criminal court, eventually leading over fifty years later to the adoption of the Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Criticism

Critics[40] of the Nuremberg trials argued that the charges against the defendants were only defined as "crimes" after they were committed and that therefore the trial was invalid as a form of "victors' justice".[41] As Biddiss[42] noted "...the Nuremberg Trial continues to haunt us... It is a question also of the weaknesses and strengths of the proceedings themselves. The undoubted flaws rightly continue to trouble the thoughtful."[43][44]

Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court Harlan Fiske Stone called the Nuremberg trials a fraud. "(Chief U.S. prosecutor) Jackson is away conducting his high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg," he wrote. "I don't mind what he does to the Nazis, but I hate to see the pretense that he is running a court and proceeding according to common law. This is a little too sanctimonious a fraud to meet my old-fashioned ideas."[45]

Jackson, in a letter discussing the weaknesses of the trial, in October 1945 told U.S. President Harry S. Truman that the Allies themselves "have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for. The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of prisoners of war that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them. We are prosecuting plunder and our Allies are practicing it. We say aggressive war is a crime and one of our allies asserts sovereignty over the Baltic States based on no title except conquest."[46][47]

Associate Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas charged that the Allies were guilty of "substituting power for principle" at Nuremberg. "I thought at the time and still think that the Nuremberg trials were unprincipled," he wrote. "Law was created ex post facto to suit the passion and clamor of the time."[48]

U.S. Deputy Chief Counsel Abraham Pomerantz resigned in protest at the low caliber of the judges assigned to try the industrial war criminals such as those at I.G. Farben.[49]

The validity of the court has been questioned for a variety of reasons:

- The defendants were not allowed to appeal or affect the selection of judges. A. L. Goodhart, Professor at Oxford, opposed the view that, because the judges were appointed by the victors, the Tribunal was not impartial and could not be regarded as a court in the true sense. He wrote:[50]

-

- "Attractive as this argument may sound in theory, it ignores the fact that it runs counter to the administration of law in every country. If it were true then no spy could be given a legal trial, because his case is always heard by judges representing the enemy country. Yet no one has ever argued that in such cases it was necessary to call on neutral judges. The prisoner has the right to demand that his judges shall be fair, but not that they shall be neutral. As Lord Writ has pointed out, the same principle is applicable to ordinary criminal law because 'a burglar cannot complain that he is being tried by a jury of honest citizens.'"

- One of the charges, brought against Keitel, Jodl, and Ribbentrop included conspiracy to commit aggression against Poland in 1939. The Secret Protocols of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 23 August 1939, proposed the partition of Poland between the Germans and the Soviets (which was subsequently executed in September 1939); however, Soviet leaders were not tried for being part of the same conspiracy.[51] Instead, the Tribunal falsely proclaimed the Secret Protocols of the Non-Aggression Pact to be a forgery. Moreover, Allied Powers Britain and Soviet Union were not tried for preparing and conducting the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran and the Winter War, respectively.

- In 1915, the Allied Powers, Britain, France, and Russia, jointly issued a statement explicitly charging, for the first time, another government (the Sublime Porte) of committing "a crime against humanity". However it was not until the phrase was further developed in the London Charter that it had a specific meaning. As the London Charter definition of what constituted a crime against humanity was unknown when many of the crimes were committed, it could be argued to be a retrospective law, in violation of the principles of prohibition of ex post facto laws and the general principle of penal law nullum crimen, nulla poena sine praevia lege poenali.[52]

- The court agreed to relieve the Soviet leadership from attending these trials as war criminals in order to hide their crimes against war civilians, war crimes that were committed by their army that included "carving up Poland in 1939 and attacking Finland three months later." This "exclusion request" was initiated by the Soviets and subsequently approved by the court's administration.[53]

- The trials were conducted under their own rules of evidence; the indictments were created ex post facto and were not based on any nation's law; the tu quoque defense was removed; and some claim the entire spirit of the assembly was "victor's justice". The Charter of the International Military Tribunal permitted the use of normally inadmissible "evidence". Article 19 specified that "The Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence... and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value". Article 21 of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal (IMT) Charter stipulated:

-

- "The Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge but shall take judicial notice thereof. It shall also take judicial notice of official governmental documents and reports of the United [Allied] Nations, including acts and documents of the committees set up in the various allied countries for the investigation of war crimes, and the records and findings of military and other Tribunals of any of the United [Allied] Nations"

- The chief Soviet prosecutor submitted false documentation in an attempt to indict defendants for the murder of thousands of Polish officers in the Katyn forest near Smolensk. However, the other Allied prosecutors refused to support the indictment and German lawyers promised to mount an embarrassing defense. No one was charged or found guilty at Nuremberg for the Katyn Forest massacre.[54] In 1990, the Soviet government acknowledged that the Katyn massacre was carried out, not by the Germans, but by the Soviet secret police.[55]

- Freda Utley, in her 1949 book "The High Cost of Vengeance"[1] charged the court with amongst other things double standards. She pointed to the Allied use of civilian forced labor, and deliberate starvation of civilians[56][57] in the occupied territories. She also noted that General Rudenko, the chief Soviet prosecutor, after the trials became commandant of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. (After the fall of East Germany the bodies of 12,500 Soviet era victims were uncovered at the camp, mainly "children, adolescents and elderly people."[58])

- Luise, the wife of Alfred Jodl, attached herself to her husband's defence team. Subsequently interviewed by Gitta Sereny, researching her biography of Albert Speer, Luise alleged that in many instances the Allied prosecution made charges against Jodl based on documents that they refused to share with the defense. Jodl nevertheless proved some of the charges made against him were untrue, such as the charge that he helped Hitler gain control of Germany in 1933. He was in one instance aided by a GI clerk who chose to give Luise a document showing that the execution of a group of British commandos in Norway had been legitimate. The GI warned Luise that if she didn't copy it immediately she would never see it again; "... it was being 'filed'."[59]

Moreover, the Tribunal itself strongly disputed that the London Charter was ex post facto law, pointing to existing international agreements signed by Germany that made aggressive war and certain wartime actions unlawful, such as the Kellogg-Briand Pact, the Covenant of the League of Nations, and the Hague Conventions.[60]

Additionally, many commentators felt the Nuremberg Trials represented a step forward in extending fairness to the vanquished by requiring that actual criminal misdeeds be proved before punishment could ensue; including some of the defendants and their legal team:

- Perhaps the most telling responses to the critics of Jackson and Nuremberg were those of the defendants at trial. Hans Frank, the defendant who had served as the Nazi Governor General of occupied Poland, stated, "I regard this trial as a God-willed court to examine and put an end to the terrible era of suffering under Adolf Hitler." With the same theme, but a different emphasis, defendant Albert Speer, Hitler's war production minister, said, "This trial is necessary. There is a shared responsibility for such horrible crimes even in an authoritarian state." Dr. Theodore Klefish, a member of the German defense team, wrote: "It is obvious that the trial and judgment of such proceedings require of the tribunal the utmost impartiality, loyalty and sense of justice. The Nuremberg tribunal has met all these requirements with consideration and dignity. Nobody dares to doubt that it was guided by the search for truth and justice from the first to the last day of this tremendous trial."[61]

In his opening statements to the trial, after the indictments had been read and the defendants had enterered pleas of not guilty to the charges, Mr Justice Jackson explained some of the difficulties faced by the prosecution:[62]

In justice to the nations and the men associated in this prosecution, I must remind you of certain difficulties which may leave their mark on this case. Never before in legal history has an effort been made to bring within the scope of a single litigation the developments of a decade, covering a whole continent, and involving a score of nations, countless individuals, and innumerable events. Despite the magnitude of the task, the world has demanded immediate action. This demand has had to be met, though perhaps at the cost of finished craftmanship. In my country, established courts, following familiar procedures, applying well-thumbed precedents, and dealing with the legal consequences of local and limited events, seldom commence a trial within a year of the event in litigation. Yet less than eight months ago to-day the courtroom in which you sit was an enemy fortress in the hands of German S.S. troops. Less than eight months ago nearly all our witnesses and documents were in enemy hands.

He also acknowledged that the trial would not be perfect, as well as asserting the legal precedent being set:[63]

I should be the last to deny that the case may well suffer from incomplete researches, and quite likely will not be the example of professional work which any of the prosecuting nations would normally wish to sponsor. It is, however, a completely adequate case to the judgment we shall ask you to render, and its full development we shall be obliged to leave to historians... At the very outset, let us dispose of the contention that to put these men to trial is to do them an injustice, entitling them to some special consideration. These defendants may be hard pressed but they are not ill used... If these men are the first war leaders of a defeated nation to be prosecuted in the name of the law, they are also the first to be given the chance to plead for their lives in the name of the law.

Legitimacy

One criticism that was made of the IMT was that some treaties were not binding on the Axis powers because they were not signatories. This was addressed in the judgment relating to war crimes and crimes against humanity[64], which contains an expansion of customary law: "the Convention Hague 1907 expressly stated that it was an attempt 'to revise the general laws and customs of war,' which it thus recognised to be then existing, but by 1939 these rules laid down in the Convention were recognised by all civilised nations, and were regarded as being declaratory of the laws and customs of war which are referred to in Article 6 (b) of the [London] Charter." The implication under international law is that if enough countries have signed up to a treaty, and that treaty has been in effect for a reasonable period of time, then it can be interpreted as binding on all nations, not just those who signed the original treaty. This is a highly controversial aspect of international law, one that is still actively debated in international legal journals.

Introduction of Extempore Simultaneous Interpretation

The Nuremberg Trials employed four official languages: English, German, French, and Russian. In order to address the complex linguistic issues that clouded over the proceedings, interpretation and translation departments had to be established. However, it was feared that consecutive interpretation would slow down the proceedings significantly. What is therefore unique both the Nuremberg tribunals and history of the interpretation profession was the introduction of an entirely new technique, extempore simultaneous interpretation. This technique of interpretation requires the interpreter to listen to a speaker in a source (or passive) language and orally translate that speech into another language in real time, that is, simultaneously, through headsets and microphones. Interpreters were split into four sections, one for each official language, with three interpreters per section working from the other three languages into the fourth (their mother tongue). For instance, the English booth consisted of three interpreters, one working from German into English, one working from French, and one from Russian, etc. Defendants who did not speak any of the four official languages were provided with consecutive court interpreters. Some of the languages heard over the course of the proceedings included Yiddish, Hungarian, Czech, Ukrainian, and Polish.

The equipment used to establish this system was provided by IBM, and included an elaborate setup of cables which were hooked up to headsets and single earphones directly from the four interpreting booths (often referred to as "the aquarium"). Four channels existed for each working language, as well as a root channel for the proceedings without interpretation. Switching of channels was controlled by a setup at each table in which the listener merely had to turn a dial in order to switch between languages. People tripping over the floor-laid cables often led to the headsets getting disconnected, with several hours at a time sometimes being taken in order to repair the problem and continue on with the trials.

Interpreters were recruited and examined by the respective countries in which the official languages were spoken: United States, United Kingdom, France, Soviet Union, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, as well as in some other case from Belgium and the Netherlands. Many were former translators, army personnel, and linguists, some were experienced consecutive interpreters, others were ordinary individuals and even recent high school graduates who led international lives in multilingual environments. It was, and still is believed, that the qualities that made the best interpreters were not just a perfect understanding of two or more languages, but more importantly a broad sense of culture, encyclopædic knowledge, and inquisitiveness, as well as a naturally calm disposition.

With the simultaneous technique being extremely new, interpreters practically trained themselves but many could not handle the pressure or the psychological strain. Many often had to be replaced, many returned to the translation department, and many left. Serious doubts were given as to whether interpretation provided a fair trial for the defendants, particularly because of fears of mistranslation and errors made on transcripts. The translation department had to also deal with the overwhelming problem of being understaffed and overburdened with an influx of documents that could not be kept up with. More often than not, interpreters were stuck in a session without having proper documents in front of them and were relied upon to do sight translation or double translation of texts, causing further problems and extensive criticism. Other problems that arose included complaints from lawyers and other legal professionals with regard to questioning and cross-examination. Legal professionals were most often appalled at the slower speed at which they had to conduct their task because of the extended time required for interpreters to do an interpretation properly. Also, a number of interpreters were noted for protesting the idea of using vulgar language reflected in the proceeds, especially if it referenced Jews or the conditions of the concentration camps. Bilingual/trilingual members who attended the trials picked up quickly on this aspect of character and were equally quick to file complaints.

Yet, despite the extensive trial and error, without the interpretation system the trials would not have been possible and in turn revolutionized the way multilingual issues were addressed in tribunals and conferences. A number of the interpreters following the trials were immediately recruited into the newly formed United Nations, while others returned to their ordinary lives, perused other careers, or worked freelance. Outside the boundaries of the trials, many interpreters continued their positions on weekends as interpreters for dinners, private meetings between judges, and excursions between delegates. Others worked as investigators or editors, or aided the translation department when they could, often using it as an opportunity to sharpen their skills and to correct poor interpretations on transcripts before they were available for public record.

For further reference, a book titled The Origins of Simultaneous Interpretation: The Nuremberg Trial, written by interpreter Francesca Gaiba, was published by the University of Ottawa Press in 1998.

Today, all major international organizations, as well as any conference or government that uses more than one official language, uses extempore simultaneous interpretation. Notable bodies include the Parliament of Canada with two official languages, the European Union with twenty-three official languages, and the United Nations with six official working languages.

Further reading

See also

- Command responsibility

- Eichmann in Jerusalem

- Einsatzgruppen Trial

- International Military Tribunal for the Far East

- Judgment at Nuremberg (1961 film)

- List of Axis personnel indicted for war crimes

- List of war crimes

- Nazi eugenics

- Nuremberg Defense

- Nuremberg Diary, an account of observations and discussions with the defendants by an American psychiatrist

- Superior Orders

- Tanya Savicheva

- Transitional justice

Notes

- ↑ John Crossland Churchill: execute Hitler without trial in The Sunday Times, 1 January 2006

- ↑ Tehran Conference: Tripartite Dinner Meeting November 29, 1943 Soviet Embassy, 8:30 PM

- ↑ United States Department of State Foreign relations of the United States. Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945. p.571

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Overy, Richard (27 September 2001). Interrogations: The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands (1st ed.). Allen Lane, The Penguin Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0713993502.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Heydecker, Joe J.; Leeb, Johannes (1979) (in German). Der Nürnberger Prozeß. Köln: Kiepenheuer und Witsch. p. 97.

- ↑ Minutes of 2nd meeting of BWCE and the Representatives of the USA. Kew, London: Lord Chancellor's Office, Public Records Office. 21 June 1945.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rough Notes Meeting with Russians. Kew, London: Lord Chancellor's Office, Public Records Office. 29 June 1945.

- ↑ Overy, Richard (27 September 2001). Interrogations: The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands (1st ed.). Allen Lane, The Penguin Press. pp. 15. ISBN 0713993502.

- ↑ Summary of the indictment in Department of State Bulletin, October 21, 1945, p. 595

- ↑ "Bormann judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judborma.asp.

- ↑ "Dönitz judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/juddoeni.asp.

- ↑ President of the Reich for 23 days after Adolf Hitler's suicide.Judgement : Doenitz the Avalon Project at the Yale Law School

- ↑ "Frank judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judfrank.asp.

- ↑ "Frink judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judfrick.asp.

- ↑ "Fritzsche judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judfritz.asp.

- ↑ "Funk judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judfunk.asp.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography, W. W. Norton & Co. 2008, pp 932-933.

- ↑ "Goering judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judgoeri.asp.

- ↑ "Hess judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judhess.asp.

- ↑ "Jodl judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judjodl.asp.

- ↑ "Kaltenbrunner judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judkalt.asp.

- ↑ "Keitel judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judkeite.asp.

- ↑ "Von Neurath judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judneur.asp.

- ↑ "Von Papen judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judpapen.asp.

- ↑ "Raeder judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judraede.asp.

- ↑ "Von Ribbentrop judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judribb.asp.

- ↑ "Rosenberg judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judrosen.asp.

- ↑ "Sauckel judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judsauck.asp.

- ↑ "Schacht judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judschac.asp.

- ↑ "Von Schirach judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judschir.asp.

- ↑ "Seyss-Inquart judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judseyss.asp.

- ↑ "Speer judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judspeer.asp.

- ↑ "Streicher judgement". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judstrei.asp.

- ↑ Goldensohn, Leon N., and Gellately, Robert (ed.): The Nuremberg Interviews, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-375-41469-X

- ↑ "Judgment at Nuremberg" (PDF). http://w3.salemstate.edu/~cmauriello/pdf_his102/nuremberg.pdf.

- ↑ "The trial of the century". http://www.law.uga.edu/academics/profiles/dwilkes_more/his34_trial2.html.

- ↑ War Crimes: Night without Dawn. Time Magazine Monday, October 28, 1946

- ↑ Overy, Richard (27 September 2001). Interrogations: The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands (1st ed.). Allen Lane, The Penguin Press. p. 205. ISBN 0713993502.

- ↑ "Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1950". Untreaty.un.org. http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/publications/yearbooks/1950.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ See, e.g., Zolo(Victors' Justice (2009) by Danilo Zolo, Professor of Philosophy and Sociology of Law at the University of Florence.

- ↑ See, e.g., statement of Professor Nicholls of St. Antony's College, Oxford, that "[t]he Nuremberg trials have not had a very good press. The are often depicted as a form of victors' justice in which people were tried for crimes which did not exist in law when they committed them, such as conspiring to start a war."Prof. Anthony Nicholls, University of Oxford

- ↑ "Victors' Justice: The Nuremberg Tribunal," by Michael Biddiss, History Today, Vol. 45, May 1995

- ↑ See, e.g., BBC Article for BBC by Prof. Richard Overy ("[T]hat the war crimes trials ... were expressions of a legally dubious 'victors' justice' was [a point raised by] ...senior [Allied] legal experts who doubted the legality of the whole process... There was no precedent. No other civilian government had ever been put on trial by the authorities of other states... What the Allied powers had in mind was a tribunal that would make the waging of aggressive war, the violation of sovereignty and the perpetration of what came to be known in 1945 as 'crimes against humanity' internationally recognized offences. Unfortunately, these had not previously been defined as crimes in international law, which left the Allies in the legally dubious position of having to execute retrospective justice - to punish actions that were not regarded as crimes at the time they were committed.")

- ↑ See Paper of Jonathan Graubart, San Diego State University, Political Science Department, published online Graubart Article, referring to the ex post facto nature of the charges.

- ↑ 'Harlan Fiske Stone: Pillar of the Law', Alpheus T. Mason, (New York: Viking, 1956)

- ↑ David Luban, "Legal Modernism", Univ of Michigan Press, 1994. ISBN 13: 9780472103805 pp. 360,361

- ↑ The Legacy of Nuremberg PBF

- ↑ 'Dönitz at Nuremberg: A Reappraisal', H. K. Thompson, Jr. and Henry Strutz, (Torrance, Calif.: 1983)

- ↑ Ambruster, Howard Watson (1947). Treason's Peace. Beechhurst Press.

- ↑ A. L. Goodhart, "The Legality of the Nuremberg Trials", Juridical Review, April, 1946.

- ↑ Bauer, Eddy The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War II Volume 22 New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation 1972 page 3071.

- ↑ "Motion adopted by all defense counsel". http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/proc/v1-30.htm.

- ↑ BBC News. 1945: Nuremberg trial of Nazis begins. November 20, 1945.

- ↑ "German Defense Team Clobbers Soviet Claims". Nizkor.org. 1995-08-26. http://www.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/places/germany/nuremberg/ftp.py?places/germany/nuremberg/tusa/katyn-hearing. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ BBC News story : Russia to release massacre files, 16 December 2004 online

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers, The United States and the Refusal to Feed German Civilians after World War II

- ↑ U.S. military personnel and their wives were under strict orders to destroy or otherwise render inedible their own leftover surplus so as to ensure it could not be eaten by German civilians. Eugene Davidson "The Death and Life of Germany" p.85 University of Missouri Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8262-1249-2

- ↑ "Germans Find Mass Graves at an Ex-Soviet Camp" The New York Times, September 24, 1992

- ↑ Gitta Sereny, Albert Speer His Battle with Truth, p.578. ISBN 0-394-52915-4

- ↑ "International Military Tribunal, Judgment of the International Military Tribunal (1946)". http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/proc/judlawch.htm.

- ↑ Robert Jackson and International Human Rights, Professor Henry T. King, Robert H. Jackson Center, 1 May 2003

- ↑ The Trial of German Major War Criminals - Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal Sitting at Nuremberg Germany. 1 (20th November, 1945 - 1st December, 1945). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1946. pp. 50.

- ↑ The Trial of German Major War Criminals - Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal Sitting at Nuremberg Germany. 1 (20th November, 1945 - 1st December, 1945). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1946. pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Judgement : The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity in the Avalon Project archive at Yale Law School

External links

- Film Nuernberg: 40 Years Later. (1986)

- Official records of the Nuremberg trials (The Blue series) in 42 volumes from the records of the Library of congress

- The Nuremberg Trials Original reports and pictures from The Times

- Official page of the Nuremberg City Museum

- Nuremberg defence doesn't make the grade-The Age newspaper

- Donovan Nuremberg Trials Collection Cornell Law Library

- Nuremberg Trials Project: A digital document collection Harvard Law School Library

- The Avalon Project

- Charter of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg trials)

- The Subsequent Nuremberg Trials

- Holocaust Educational Resource

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Online Exhibit

- Special focus on The trials - USHMM

- Famous World Trials - Nuremberg Trials

- Nuremberg Trials Gallery

- The Nuremberg Trials: The Defendants and Verdicts

- Nuremberg War Crimes - Trials

- Nuremberg Trials 1945-1949

- "American Experience: The Nuremberg Trials" PBS

- Obituary of Anthony Marreco

- Crimes, Trials and Laws

- A Tree Fell in the Forest: The Nuremberg Judgments 60 Years On, JURIST

- Bringing a Nazi to justice: how I cross-examined 'fat boy' Göring, guardian.co.uk

- CBC Radio: A Conversation with Geoffrey Robertson, Author of the Tyrannicide Brief (Feb 18/07) (RealAudio)

- JAG Corps Attorneys

- Attorney Shawcross reads an account of a massacre - 27 July 1946 (BBC) (Windows Media and Real Audio) Warning: graphic descriptions of atrocities

- The Nuremberg Judgments, Chapter 6 from The High Cost of Vengeance, by Freda Utley, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, (1948). Made available by "The Freda Utley Foundation"

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||